Fungal networks in the forest: evidence for Wood Wide Web

An international research team with the participation of the University of Bayreuth sees mycoheterotrophic plants as the key to the previously controversial existence of the underground mycorrhizal network in forests.

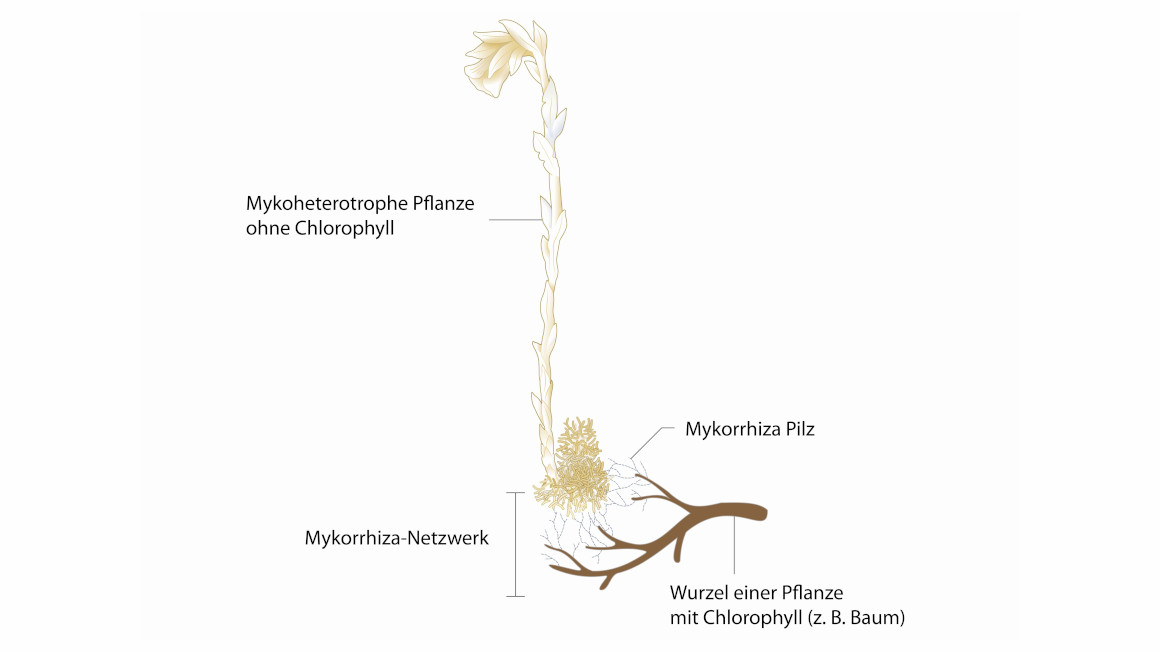

The majority of land plants live in symbiosis with mycorrhizal fungi. The fungal networks on the roots supply the plants with important nutrients such as phosphorus and nitrogen as well as water from the soil. In return, the fungus is nourished with carbon, which the plant obtains and contributes from photosynthesis. Studies have already confirmed the importance of this biocoenosis for plants, fungi and ecosystems.

However, the fact that forests in particular could be permeated by entire networks of plant roots and fungal tissue has been controversial in the scientific community to date. An international consortium involving the University of Bayreuth has now provided proof of the existence of this so-called Wood Wide Web as well as its function and significance. The researchers report on their work in the scientific journal "Nature Plants".

Mycoheterotrophic plants provide evidence for Wood Wide Web

As part of the study, the researchers critically examined the significance of the underground network and scoured the specialist literature for evidence of the existence of the Wood Wide Web. They found that one important group of plants had been largely overlooked until now, but which, according to the scientists, "provides very obvious evidence for the existence of mycorrhizal networks" – namely mycoheterotrophic plants.

Unlike autotrophic plants, which include green plants, mycoheterotrophic plants do not obtain carbon from the plant's photosynthesis, but from a fungal partner. The research team has now taken a closer look at these small forest plants, which have received little attention to date.

Mycorrhizal fungi form further symbiosis with forest trees

According to the study, mycoheterotrophic plants do not have green leaves and therefore have to feed themselves entirely at the expense of mycorrhizal fungi. However, these fungal partners simultaneously enter into a second partnership with forest trees and thus mediate the carbon exchange between the plants. Although these mycoheterotrophic plants are usually small and easily overlooked on the forest floor, they provide crucial evidence for the importance of the "Wood Wide Web", as mycorrhizal networks in forests support carbon transfer between plants, the researchers write.

"The fully mycoheterotrophic plants thus prove the existence of mycorrhizal networks in which at least three partners – two plants and a fungus – are involved," says Bayreuth researcher Gerhard Gebauer, who worked on the study together with his colleague Franziska Zahn.

Carbon transfer possible in various ways

These findings would not only call into question the previous doctrine of carbon versus nutrient transfer in the symbiosis between a fungus and a plant. The assumption that all green plants feed themselves strictly by obtaining carbon via photosynthesis must also be questioned. As the researchers write, there is a wide range of possibilities for carbon transfer.

In addition to completely mycoheterotrophic plants, which obtain carbon exclusively from the fungal partner, and autotrophic plants, which obtain carbon exclusively from photosynthesis, there are also plants, according to the researchers, "which feed to varying degrees at the expense of the fungal partner and from photosynthesis".

bb